The night before the Great Panathenaea, there was a vigil, with dancing by young men and girls. At sunrise on the twenty-eighth of Hekatombaion - Athena's birth day - the torch-race started. The object was to bring the new fire from the grove of Academus, beyond the city walls, to the altar of Athena on the Acropolis. There followed a grand procession, in which the whole citizen population took part. Its starting-point was the Kerameikos; its finishing-point was the Acropolis; and its purpose was to transfer offerings to Athena, principally the sacred peplos destined to clothe the wooden image of Athena Polias.

|

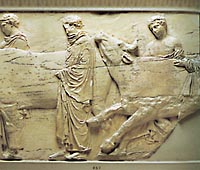

The peplos was a huge rectangular textile showing the Gigantomachy ('Battle of Gods and Giants'). It was woven every year by women of Athens - the so-called ergastinai under the supervision of the woman priest of the god. This was the same subject that appeared on the pediment of the temple of Athena on the Acropolis in Pisistratus' time. It was linked with the myth of the distinguished part played by Athena in the Battle of the Gods and the Giants. The textile was unfurled like a sail on a ship-on-wheels. The ship made its way through the Agora. When it reached the Areopagus hill, the peplos was taken down and carried onward by hand, to be entrusted to the male priests who had the task of wrapping it round the god's likeness. Those who took part in the procession were women (kanephoroi) with baskets of offerings for the god; elderly men (thallophoroi) holding branches of olive; young male riders and other males (skaphephoroi) with vessels called skaphai; and women or young girls (hydriaphoroi) carrying a water-jug on the shoulder. The donation and transport of these vessels was a metic privilege. In the procession there were also Athena's sacrificial animals - she-goats, rams, bulls, cows, and sheep. It is the procession of the Great Panathenaea which has been seen by most scholars as the scene portrayed on the Parthenon frieze. |

|

|

|

| |

|||

| |||